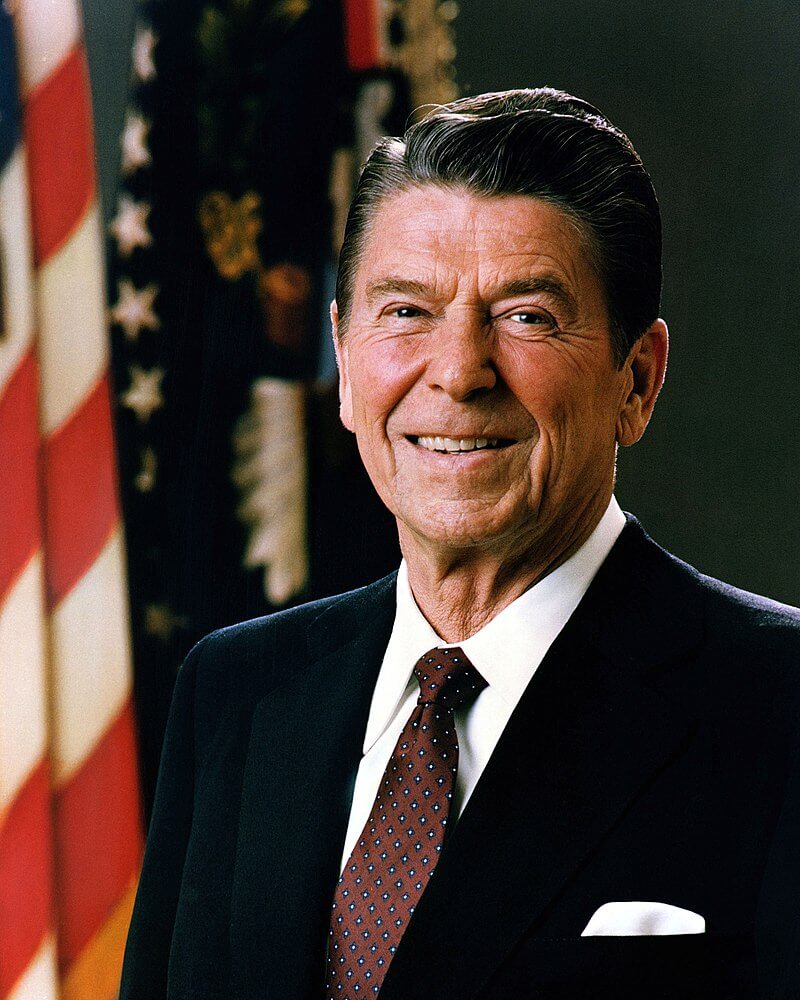

I hope you are all Republicans.

When Ronald Reagan went into surgery, after being shot by John Hinckley, he removed his oxygen mask long enough to joke, “I hope you are all Republicans.”

That line is classic enough, but what has cemented it into presidential lore is the response of one of the surgeons who said, “Today, Mr. President, we are all Republicans.”

The modern executive

Peter Drucker, one of the great management theorists of the 20th century, wrote a book called The Effective Executive.

Now, you might be wondering what a book about executives has to do with you, after all, most of us people aren’t executives, but listen to who Peter Drucker says is an executive:

Every knowledge worker in modern organization is an executive if, by virtue of his position or knowledge, he is responsible for a contribution that materially affects the capacity of the organization to perform and to obtain results. This may be the capacity of a business to bring out a new product or to obtain a larger share of a given market. It may be the capacity of a hospital to provide bedside care to his patients, and so on. Such a man (or woman) must make decisions; he cannot just carry out orders he must take responsibility for his contribution. And he is supposed, by virtue of his knowledge, to be better equipped to make the right decision than anyone else. He may be overridden he may be demoted or fired. But so long as he has the job the goals, the standards, and the contributions are in his keeping.

If Drucker were here today looking over the tech industry, for instance, I think he would say something similar to what that surgeon said to Reagan:

Today, we are all executives.

Drucker wrote his book in 1967, so, he was on the front end of the revolution in work we’ve experienced over the past 50 years. He looked at how corporations were changing in his own time and he peered around the corner, and the future he saw looked radically different from his present.

It looked like a future where everyone made decisions that affected the direction of their company. It looked like today.

If we just look at the tech industry as one example of this trend we can see the truth in Drucker’s insight. If you are a software engineer your work directly affects the success of the company you’re at. The things you are building day in and day out are what your company is built upon.

The same is true if you’re product owner, scrum master, designer, or anything else.

Thinking more about software engineers: you might have a general design of what you’re supposed to build, but how you get to the end result is largely up to you.

There’s a tremendous amount of leeway where your domain knowledge is applied to the problem you’re facing.

Contrast that with the 20th century factory worker who could spend decades doing the same thing every day. The key point of leverage was speed and efficiency at accomplishing their task.

That isn’t true for knowledge work.

Yes, bringing a large amount of resources to bear on a problem might be the right decision, but it’s not always as clear cut as it was in 1950s Detroit.

The story of the technology industry has been one of small groups of individuals disrupting much larger incumbents.

Drucker recognized this:

Two hundred people, of course, can do a great deal more work than one man. But it does not follow that they produce and contribute more. Knowledge work is not defined by quantity. Neither is knowledge work defined by its costs. Knowledge work is defined by its results. WhatsApp had 200 million users and 50 employees. That kind of impact can’t come from an organization that only has a few executives. Such a company is composed entirely of executives.

Amazon has made this a cornerstone of their structure. Jeff Bezos calls it the “two pizza rule.”

It’s a simple idea: if a team can’t be fed by two pizzas, it’s too big. We tend to think bigger is better, but here one of the most successful companies in the world has adopted a policy of keeping teams small.

As smaller teams run larger products and bigger companies the responsibilities of each individual contributor grows exponentially.

The idea of a worker bee who blindly does the same task day after day is dying out. In many organizations such a role doesn’t exist.

Modern companies are not composed of drones but executives.

A new reality

The new reality is that everyone is an executive. So what do we do?

And how do we learn to effectively wield our newfound responsibilities?

We might be tempted to look to what modern writers are saying on this subject, and while that wouldn’t be wrong we’ll be returning to something a bit older.

Remember, Drucker wrote The Effective Executive in 1967.

He offers a vision on how the executive can move from ineffectiveness to effectiveness.

And while in the era he wrote his book the executive looked something akin to Don Draper in Mad Men the number of people today who fit his definition of an executive has ballooned to encompass many millions more.

For as he says:

“Executives” [are] those knowledge workers, managers, or individual professionals who are expected by virtue of their position or their knowledge to make decisions in the normal course of their work that have significant impact on the performance and results of the whole.

That definition covers a lot more than simply C-suite (CEO, COO, CTO, etc.) executives.

Drucker is going to whip us into fighting shape and show us tools that we must learn and we’ll explore in depth:

- Time management

- Choosing our contribution

- How to use strength

- Finding the right priorities

- Making good decisions

If today we are all executives, then, we best learn how to be effective ones.

- Introduction to The Effective Executive

- Today, we are all executives (you are here)

- Why you are ineffective